Mastitis

Put simply, mastitis refers to inflammation of the mammary gland (udder). Mastitis is generally considered the most costly production disease of dairy cows. It affects the farmer financially in several ways;

-Discarded milk

-Veterinary and drug costs

-Increased culling

-Reduced production for the remainder of the season due to permanent damage to the secretory tissue

-Penalties in milk price due to changes in milk quality and elevations in somatic cell count

Most inhibitory substance grades are caused by intramammary antibiotics.

Classification of Mastitis

For purposes of defining the source of infection, mastitis is classified as contagious mastitis or environmental mastitis. Contagious mastitis results from bacteria that are transmitted from cow to cow i.e. the bacteria are present on the udder of cows. Environmental mastitis originates from bacteria in the cow’s environment, i.e. a contaminated paddock.

Mastitis is also classified as clinical mastitis (disease with visible changes in the milk) and subclinical mastitis (disease that is not visibly apparent). The great majority of cases are subclinical. Because it is not obvious, dairy producers may not be aware of subclinical mastitis and the extent of lost milk production that results. Undetected subclinical mastitis can also be a source of infection to other cows, will elevate Somatic Cell Count (SCC) and decrease production.

Clinical mastitis is characterised by the following;

-Rapid onset, heat, swelling, reddening, or hardening of infected quarters. This is painful.

-Visible abnormalities in milk, including clots, flakes, or discolouration.

-In acute cases systemic signs, including fever, anorexia and reduced rumination, dehydration, weakness, depression, and noticeable decline in milk production.

-The cow may be lame due to swelling of the udder

Subclinical mastitis is characterised by the following;

-No visible change in the udder or in appearance of the cow

-No visible abnormalities in milk

-Reduced milk yield in the affected quarter(s)

-In some cases, periodic episodes of clinical mastitis in affected cows

-Elevated Somatic Cell Count (SCC) and Bulk Tank Somatic Cell Count (BTSCC)

Acute mastitis: refers to sudden onset with severe clinical signs

Chronic mastitis: persistent or recurrent with mild or no clinical signs

Gangrenous (black) mastitis – This is caused by certain bacteria that produce nasty toxins restricting blood flow to the affected quarter. This results in a blue/ black quarter that is cold to the touch. The toxins from the bacteria and the dying udder tissue are absorbed into the body and consequently these cows become severely ill and often go down.

Antibiotics are usually unsuccessful as they have no effect on toxins. The majority of animals with black mastitis are euthanized or die.

Structure of the Udder and Milk Synthesis

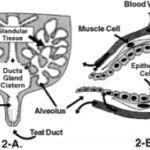

The udder is derived from a highly modified sweat gland. Milk is produced by small, sac-like structures deep within the tissue called alveoli. Each milk producing cell is surround by muscle, which when stimulated by oxytocin, contracts and squeezes milk into the gland. The milk then flows into the cistern and down the teat.

Milk synthesis is a complex process that involves the rumen, liver and udder. The liver produces glucose from products of remen fermentation. The glucose is transported to the udder where it is converted into lactose. The amount of lactose in the milke controls milks volume.

Milk protein & casein is also made in the udder from components of rumen fermentation. Milk protein concentration is determined by the amount of energy rather than the protein in the diet. Milk fat is synthesized in the udder as well. The components are derived from the fermentation of fibre in the diet, bypass fat and the mobilisation of body fat (during early lactation). Adequate fiber is therefore essential for milk fat production.

How does mastitis affect milk synthesis and quality?

When the udder becomes infected and inflamed there is significant injury and damage to the milk producing cells of the udder. The cow’s immune system responds to the infection by sending billions of white blood cells (pus) into the udder. It is the white blood cells that make up 98% of the somatic cell count. Infection = increase in SCC. In addition to this influx of cells, there are significant changes in milk composition such as decreased lactose, protein and fat and increased salt. Several enzymes leak into the milk from the damaged cells. This leads to rapid breakdown and rancidity of milk.

The influx of cells that occurs with infection provides a measure of milk quality and can be assessed by either counting them in 1000’s per milk or using the Rapid Mastitis test (RMT – see notes). Similarly the increased salt concentration improves the conductivity of milk and is the principle for electronic mastitis testers.

As a result of all these changes, milk from cows with mastitis is not suitable for the production of certain products and for this reason the dairy companies have payment incentives and penalties in place.

Major Mastitis Players in New Zealand

The majority of mastitis is caused by 2 different species of bacteria; Streptococcus uberis & Staphylococcus aureus.

Coliforms (E. coli), Strep agalactiae & Strep dysgalactiae occasionally cause mastitis.

Streptococcus uberis

-This is the most important mastitis pathogen in the pastoral dairying systems of NZ

-Environmental mastitis

-Most infections occur during the early dry period and in the first 6 weeks after calving

-Very sensitive to penicillin being 95% effective and therefore good cure rates

-Subclinical infections are uncommon

-SCC are not as high as with staphylococcus infections

-Main cause of heifer mastitis

Detection of Mastitis

The early detection and treatment of all quarters with clinical mastitis reduces the risk of severe mastitis developing, reduces the likelihood of infection being spread from cow-cow and reduces the risk of an increase in BMSCC.

Methods of Detection

Visual

Changes in the behaviour of the animal; slow to walk in, lame, kicking cups off

Changes in the milk; watery, blood, clots or flecks

Changes in the udder; hot, swollen, asymmetrical, tender

Clots on the filter sock

SCC

Individual SCC (herd test results) are very useful for detecting subclinical mastitis and chronically infected cows

Rapid Mastitis Test (RMT)

Used to identify which quarter/s is involved, screening for milk quality, SCC after calving before putting cow’s milk into the vat

Electronic Mastitis Test (Conductivity Meters)

Works on the salt levels within the milk. Many are available. Care is required with interpretation.

When to Use each Test

After Calving – After the compulsory withholding period of 8 milkings, test cows with RMT or mastitis meter before adding their milk to the vat. Heifers may take up to 10 days before SCC is down and RMT is negative. Introducing heifers into the too early after calving is often the reason for getting high SCC grades early in the season when milk volume is low

High Bulk Somatic Cell Count – strip all cows before cupping to find infected quarter/s. If nothing detected, use RMT or conductivity meter on whole herd

Herd Test Results – used to identify high SCC cows. Use RMT or conductivity meter to then identify affected quarter/s

Control and Prevention of Mastitis

Pre-Calving Management

Cows are very susceptible to infection around calving because their natural defense mechanisms are low. New infections occur, and subclinical infections which have persisted through the dry period may flare up into clinical cases. Induced cows are even more vulnerable to mastitis infections because their immune systems have reduced efficiency at that time.

Around calving, the udder is often filled with milk for relatively long periods without the flushing effect of being milked. Bacteria may enter the end of the teat, particularly if high udder pressure opens the teat canals. They can then multiply and establish infections. High numbers of environmental mastitis bacteria may contaminate teats, especially if udders are wet and exposed to mud and manure. This can happen easily when cows and heifers are on the ground during calving.

Because of the high incidence of mastitis in the first month after calving, special care in this period will pay off.

Draft springing cows (transition cows) into a separate mob

Give a bigger break to avoid pugging and contaminating the environment

Need to feed well above maintenance to allow for the rapidly growing foetus. Introduce some of the feed that will be given after calving, to give the rumen flora time to adjust to the new diet

Any cow or heifer really tight and dripping milk can be milked just enough to take the pressure off. Teat spray thoroughly afterwards

Once calved, separate immediately from calf and milk out properly

Oxytocin can be used if animals are reluctant to let their milk go after a few milkings, or in case of mastitis. It will aid in milk let-down and emptying of the glands.

Lactation Management

Avoid pre-washing teats unless very badly soiled

Keep hands clean. Wear gloves! Bacteria live within the cracks of milkers hands and are transferred from cow-to-cow. Bacteria are far less likely to survive on latex

Teat Spray

Apply at every milking for the entire season. It is one of the most effective cell count and mastitis control measures available, if applied correctly

To be effective the spray needs to be applied as soon after cup removal as possible

Failure to cover the whole teat of every cow at every milking is the most common error in teat disinfection

Use a high concentration (30%) of emollient during the first few months to prevent cracking which can harbour bacteria

Treating Cows

Mastitis cows should always be kept separate from the herd, and milked and treated last. A cluster that has been on a mastitis cow can potentially infect the next 8 cows being milked on that cluster!

Disinfect cluster and hands before moving to next cow

Milking Machines

Get machines checked at least once a year. Teat end damage, black pock, sore and teat end eversion are signs there may be issues with the milking machine or milking management.

Dry Cow Therapy

The most effective way to treat contagious Staph mastitis

Reduces dry cow mastitis to virtually zero

It is now compulsory for farmers to have an annual Dry Cow Consultation with their veterinarian who will help you decide which product to use and which cows to treat

Culling

Strategic culling of repeat offenders

R.M.T. Guide and Instructions

Most intramammary infections are subclinical therefore clinical examination of quarters cannot be used to differentiate between infected and non-infected quarters. The Rapid Mastitis Test (RMT) is a quick, cheap & simple test that can be conducted cow-side to help detect subclinical mastitis.

Test Procedure

-Direct 2-2 squirts of millk from each qaurter into the appropriate section on the paddle

-Add equal parts of RMT reagent and gently mix by swirling for about 10 seconds

Reading the Test

A positive reaction from a subclinical quarter/s will form a slime/gel. The greater the inflammation the thicker the slime

Milk containing a cell count of 1 million/ml or more will turn the test sample to a thick jelly

RMT tests conducted on treated quarters may show positive results for a week after a successful treatment

NB: The RMT test is a subjective measure of subclinical mastitis. What I may call a 3 a second observer may call a 2. The accuracy of the result will improve if the same person is performing the test regularly.

Recording the Test (see over)

Quarters with scores of 2-3 require treatment

Reading Score Meaning

No slime 0 Normal and healthy

Slime 1 Slight thickening which disappears with paddle movement

Thick Slime 2 Infected quarter

Heavy Slime/Clot 3 Heavily infected